For

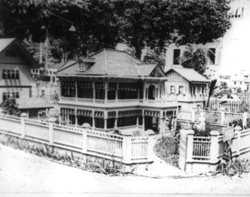

years, visitors wandering through the Bangkok’s Monk’s

Hospital gardens were surprised to stumble on a miniature city seemingly

transported from the 19th century. Beneath sheltering boughs, streets

a hands-breadth wide and lit by tiny lamps wound past dozens of

exquisitely-crafted houses. Or crossed bridges spanning canals filled

with sampans and barges. This tiny city appeared to be a collection

of doll houses, but why here in the grounds of a hospital for Buddhist

priests? For

years, visitors wandering through the Bangkok’s Monk’s

Hospital gardens were surprised to stumble on a miniature city seemingly

transported from the 19th century. Beneath sheltering boughs, streets

a hands-breadth wide and lit by tiny lamps wound past dozens of

exquisitely-crafted houses. Or crossed bridges spanning canals filled

with sampans and barges. This tiny city appeared to be a collection

of doll houses, but why here in the grounds of a hospital for Buddhist

priests?

From its rather regal appearance, few would have guessed that

the purpose of this city called Dusit Thani was to show that no

matter the class into which one had been born, all citizens were

equal before the law in a democratic society.

Its

creator was King Vajiravudh who ruled Siam (or Thailand as it

would be known after World War II) from 1910 to 1925. As a student

in England while his father, King Chualongkorn (1868-1910) still

reigned, the young prince became imbued with democratic ideals.

Soon after he assumed the throne in 1911, King Vajiravudh turned

to the West for ideas with which to carry on the modernizations

begun by his father and grandfather, Mongkut, regarded as the

most advanced Asian monarchs of the age. Its

creator was King Vajiravudh who ruled Siam (or Thailand as it

would be known after World War II) from 1910 to 1925. As a student

in England while his father, King Chualongkorn (1868-1910) still

reigned, the young prince became imbued with democratic ideals.

Soon after he assumed the throne in 1911, King Vajiravudh turned

to the West for ideas with which to carry on the modernizations

begun by his father and grandfather, Mongkut, regarded as the

most advanced Asian monarchs of the age.

He was especially enthusiastic about innovations in transportation

and communications. In 1912 he sent several Thai men to France

to learn how to build and fly airplanes. In 1914, they returned

to Thailand to establish one of Asia's first air forces. In support

of the Allied cause, he sent Thai troops to shiver in European

trenches during World War I. Inspired by England’s Boy Scouts,

he formed the Wild Tigers Corps to instill in young Thai boys

the ideals of loyalty, duty, and service to one's country.

He

also sought to introduce democracy ideals, an initiative which

would have far-reaching consequences. In his newspaper, the "Siam

Observer", he encouraged Thais to criticize government policy

and to participate in governing the country, writing many of the

critical articles himself. He

also sought to introduce democracy ideals, an initiative which

would have far-reaching consequences. In his newspaper, the "Siam

Observer", he encouraged Thais to criticize government policy

and to participate in governing the country, writing many of the

critical articles himself.

One of his most unusual initiatives was the creation in 1918

of Dusit Thani in 1918. Named after the fourth of the six levels

of the Buddhist heaven, it was designed as an exercise in model

city planning and administration.

Sited on one acre of the royal Amporn Gardens near the present

Parliament building, its buildings were scaled to one-fifteenth

life size. Within its walls were palaces, hospitals, hotels, parks,

flying bridges, a clocktower, 12-story buildings, a fire brigade,

a newspaper, trade centers, a bank, canal locks, and all the advanced

technology of a modern city of the day.

Bangkok’s noble families were encouraged to hire carpenters

to reproduce their homes in miniature. Materials and labor costs

for

a tiny stone or wooden mansions 80 to 100 centimeters tall and

decorated with delicate filigree often came to 500 baht, a fabulous

sum in those days.

Dusit

Thani's primary purpose was to demonstrate how a democratic government

functioned. According to a constitution written by the King, it

was administered by a two-party electoral system with representatives

selected by general elections. Unfortunately, Vajiravudh’s

death in 1925 halted his endeavors and the project never reached

maturity. Dusit

Thani's primary purpose was to demonstrate how a democratic government

functioned. According to a constitution written by the King, it

was administered by a two-party electoral system with representatives

selected by general elections. Unfortunately, Vajiravudh’s

death in 1925 halted his endeavors and the project never reached

maturity.

Yet Vajiravudh’s liberal attitudes remained strong, so

much so that Thai students returning from Europe where democratic

and socialistic ferment was at its height took the ideals to their

logical conclusion. Seven years after Vajiravudh's death, the

students (many of whose education had been financed by Privy Purse

scholarships), staged a revolution to topple Vajiravudh’s

successor, King Prajadipok, and established a new government that

replaced 700 years of absolute monarchy. Henceforth, Thai kings

would serve as constitutional monarchs, a play the roles of figureheads

rather than political leaders.

Dusit Thani suffered a different fate. Poorly maintained after

the king's death, it fell into disrepair. The few surviving buildings

were eventually moved to the gardens of the Monk’s Hospital.

Ultimatelyt, even they fell to dust and were swept into the trashbin.

Today, nothing remains of it except a tiny bandstand. |